Are Clinicians Really Burning Out From Poor EHR Usability?

In the previous blog article, we encountered physician burnout as a burning topic in healthcare. In this article, we explore the problem to understand what role technology can play in solving it before moving on to the requirements for an AI-based solution in future blog articles. Let’s get started.

The first physician we spoke to as part of our user research was a leading obstetrician in a large healthcare system in the San Francisco Bay Area. The first words out of her mouth were “Clinician attrition and burnout is the top issue for me and my CEO”. That surprised us, but not as much as what she said next. She also stated that technologies they use, specifically EHR systems, make her team’s life harder, not easier because they were difficult to use. This, in her opinion, was a major contributor to burnout. Therefore, from a clinician’s perspective, burnout was a problem partly caused by technology. For the naïve technologists in us, who think technology is always the solution, I realized there was more to the problem than meets the eye and we needed to spend more time understanding the problem.

Our first priority was to find additional evidence corroborating the anecdotal problem statement we were hearing from the dozens of clinicians we spoke with. The trouble is usability and burnout are both difficult to quantify and are context dependent. However, biomedical scientists investigate a large number of areas and are prolific publishers as evidenced by the fact that over a million papers are published in PubMed every year, with the number increasing by 8-9% every year. A recent paper published by Melnick, et al, reported a direct association between EHR usability and physician burnout. They used the most widely used metrics to measure usability and burnout, which we will go over briefly before getting to their results.

Measuring Usability

-

I think that I would like to use this system frequently.

-

I found the system unnecessarily complex.

-

I thought the system was easy to use.

-

I think that I would need the support of a technical person to be able to use this system.

-

I found the various functions in this system were well integrated.

-

I thought there was too much inconsistency in this system.

-

I would imagine that most people would learn to use this system very quickly.

-

I found the system very cumbersome to use.

-

I felt very confident using the system.

-

I needed to learn a lot of things before I could get going with this system.

Due to its simplicity, SUS has been used not only for software and web user interfaces, but also for hardware and voice-based interfaces. There is a process of administering, measuring, and interpreting the final score, but those topics are not in the scope of this article. The output of the process is a score normalized to a 1-100 scale with higher scores indicating easier use. For our purposes, it is sufficient to know that SUS is a simple survey that has evolved into a reliable method of measuring usability, even if it cannot be used to diagnose usability issues.

Measuring Burnout

As with SUS, there is a procedure for administering the survey, collecting data, and interpreting the results. Maslach attempts to categorize people into one of five buckets based on their scores along the three dimensions mentioned above.

-

Burnout: negative scores on exhaustion, cynicism, and professional efficacy

-

Overextended: strong negative score on exhaustion only

-

Ineffective: strong negative score on professional efficacy only

-

Disengaged: strong negative score on cynicism only

-

Engagement: strong positive scores on exhaustion, cynicism, and professional efficacy

Association between Usability and Burnout

They went a step further and plotted the median SUS by specialty and percent burnout measured using MBI by specialty to see if there was a potential relationship between the two, and the results were unsurprising. After controlling for age, sex, medical specialty, practice setting, hours worked, and number of nights on call per week, physician rated EHR usability was independently associated with the odds of burnout, with each 1-point higher SUS score associated with 3% lower odds of burnout. Overall, what we heard from dozens of users, was consistent with what was observed with 70% of a randomly selected subset of physicians, and assuming the sample is representative, 70% of all physicians across the board. If we needed proof that EHR usability causes burnout, this result was the proverbial "smoking gun".

What next?

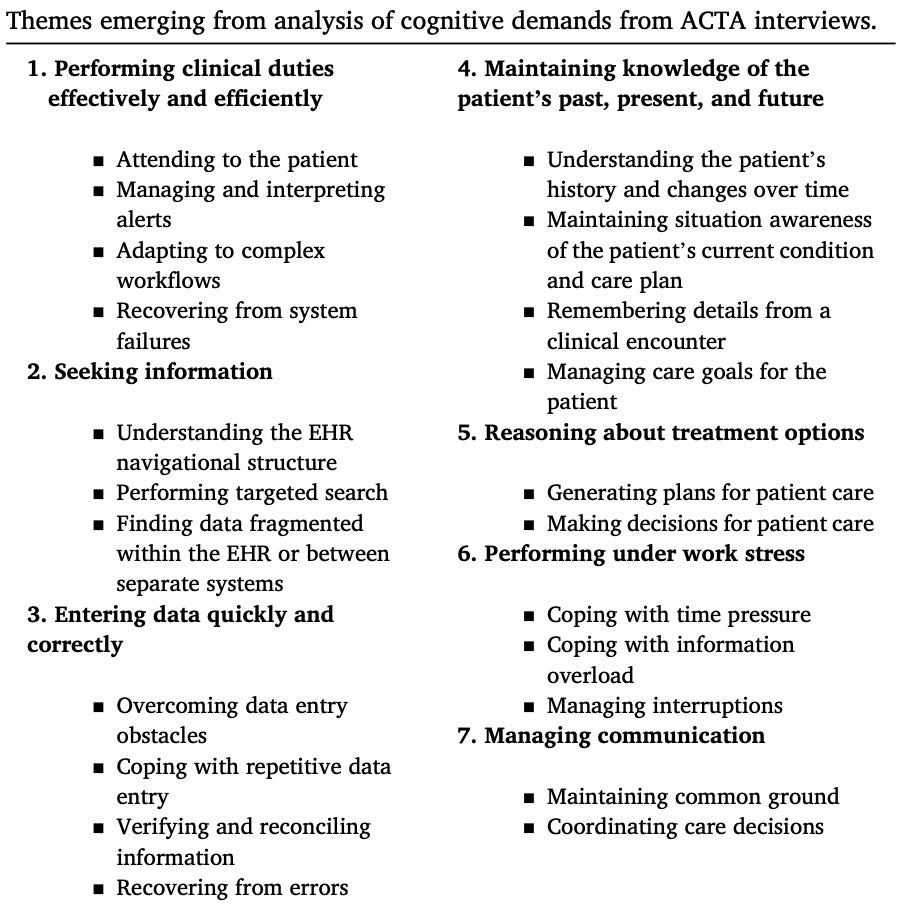

Pfaff, et al, took a more comprehensive approach to studying the cognitive demands of EHR use. They began by examining EHR use in the context of the overall caregiving process, cataloging 22 cognitive demands across seven themes, which are summarized below.

Their main conclusion was that current EHR systems do not assist physicians in creating and maintaining the big picture about patients. They also do not support clinicians' need to reason about potential treatments before making decisions, and they make collaboration difficult.

To answer the question posed in the blog's title, we believe there is evidence that poor EHR usability contributes to physician burnout. One possible explanation is the cognitive demands that EHRs currently place on clinicians. Our thesis is that the solution to many of these cognitive demands, especially those that will benefit from enabling System 1 thinking, are well suited for GenAI systems. However, many challenges remain in taming these systems to be robust, reliable, repeatable, and efficacious. These are topics for future postings.

Leave a Reply